By Margaret Rice, friend of Jill’s and fellow graduate of the Class of 1976

So many of us will never see pink and teal together, without thinking of Jill Emberson. Which is good. That’s what she wanted – for all of us to think about that colour combination forever – or at least until the change it symbolises has come.

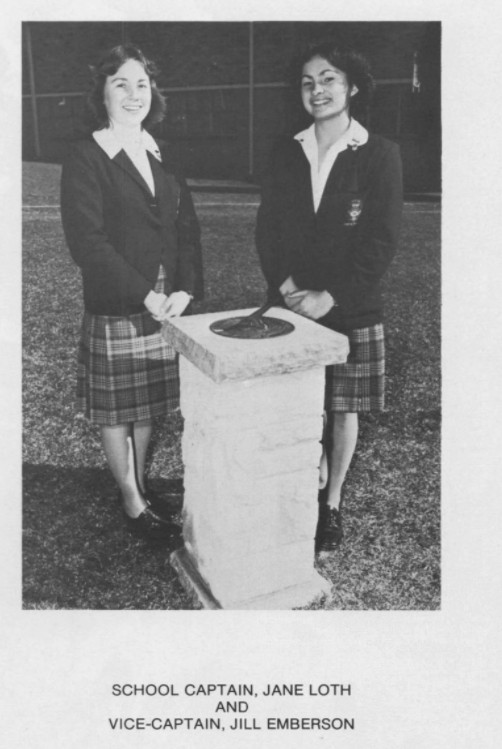

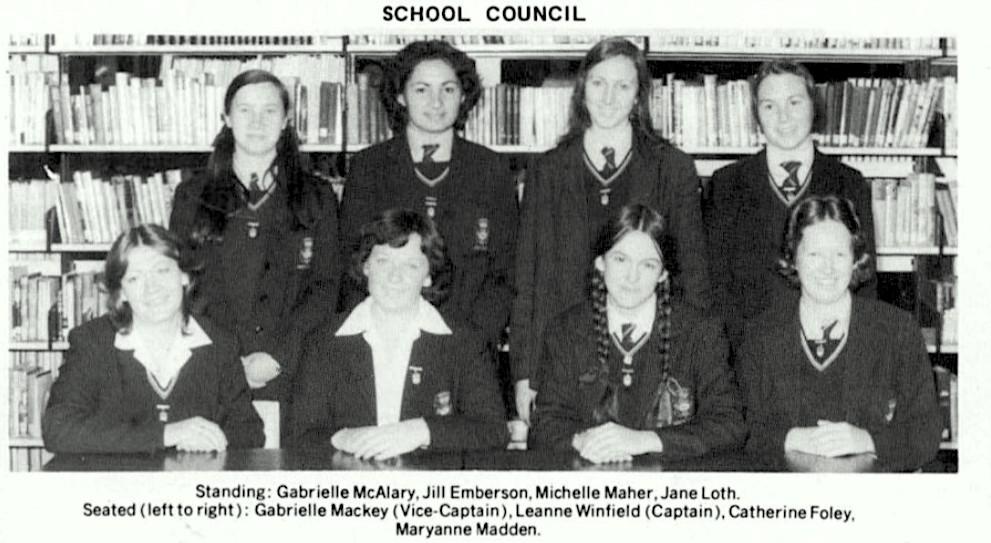

Jill, vice-captain of our year, graduated from Santa Sabina in the class of ’76. Our school years were an intoxicating time. When we started in 1971, the nuns who taught us knew change was coming to the lives of young Catholic women. As our school years passed, the Vietnam War dominated the headlines, we watched Molly Meldrum’s Countdown, read Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch.

School days rolled by against the colourful backdrop of Gough Whitlam’s prime-ministership before we studied the events of his 1975 dismissal in our modern history classes as they played out in that turbulent year.

While these social and political events had their impact on Jill, more personal influences worked on her too.

When Jill was introduced by Richard Fidler for ABC Radio’s Conversations in 2018, now that she was campaigning for better ovarian cancer funding, he said: ‘Jill was raised by a single mum, who paid for her three children to be educated in Catholic schools by driving nuns to appointments across Sydney.’

We have to excuse Fidler’s poetic licence here. Jill’s mum, Elizabeth Moore, was intelligent and hip. She was the personal assistant to the executive team at Summer Hill’s Allied Mills and she worked hard to pay the Santa Sabina school fees.

Jill was born in Inglemere a small maternity hospital in Homebush, a year after her sister Judy-Ann. A short while later her parents and the two little ones moved to England. But 12 months later, Elizabeth, pregnant with Stuart, returned to Homebush, where she was to resettle with her parents Alma and Frank, who helped and supported Elizabeth while she brought up the children.

Elizabeth chose Del Monte and Santa Sabina: ‘Because this is the education I wanted for the children, to start them in life.’

So Fidler is partly right. Jill’s awareness of herself as the daughter of a sole parent caused her to see herself as more than a cookie-cutter private school girl. By the time Jill was elected school vice-captain, she was savvy, self-aware, forward thinking and excited by social change.

Jill didn’t know her father very well then. But a little later, sitting on a south coast beach, she explained the importance to her father’s Tongan culture of public discourse and oratory. It was a statement made unselfconsciously, before any of us knew what our futures held. Yet with the sharing of that idea, came a deep realisation of self for Jill.

Jill studied media at UTS and presented on its community radio station, 2SER. After that Jill walked into a job in sales with Travelodge but walked right out of it again, realising it wasn’t for her.

She quickly shifted gear, landing where she knew she should have been in the first place, the national broadcaster, the ABC. In 1983 she started there as a reporter and presenter for the funky Triple J radio station. After five years she moved to Quantum, the very popular ABC TV science program, before eventually leaving to pursue other interests.

An early time living in Paris led to a lifelong passion for speaking French, in which Jill became very fluent. She began exploring her Tongan heritage more intensely, and at the same time worked for five years in the role of Women’s Communications Officer for the South Pacific Commission.

There was a pod of close friends she made at this time who like her, were very committed social issues journalists and together they became fearless.

As Jill’s career developed, she learnt to straddle advocacy journalism and more commercial roles. So she worked, for example, as the communications manager for Greenpeace but also later with Mark Bouris’s Wizard Home Loans.

Not long after Wizard was sold to General Electric, Jill became keen to realign with the ABC, thrilled to land in Newcastle where an opportunity presented itself to host ABC Local Radio Newcastle’s morning program.

The social justice values Jill learnt first-hand from the Dominicans always animated her, even though these were honed and refined by other influences.

Jill often came back to Santa Sabina. When she spoke to the debut girls of 2013, as guest of honour, she pointed out that she wagged school the day before she was elected vice-captain.

In that speech she also revealed how Dominican values influenced her, explaining how she interviewed the CEO of a company that had just won a second contract to provide settlement services for refugees arriving in Newcastle.

‘Within an hour an irate listener came into the station with a dossier of complaints about that very company: graphic photos of dirty, run down houses with cheap bedding, rotting pipes and gut wrenching accounts of refugees who were suffering in silence in those houses.’

‘On returning to my desk after the show, I made a cursory glance at the editorial table, but I stopped in my tracks when our complainant boomed in my direction: “I will not let a Dominican reveal only half the truth.”’

‘Who was this woman? Was she talking to me? How did she know about my Dominican origins? It turned out that our irate listener was Sr Diana Santelben, a Dominican nun who had been training at Del Monte when I was in infants school. I was gobsmacked. Sr Di had heard my original interview and wanted to engage me in her cause to bring this company to account.’

‘She runs a support service for refugee families in Newcastle and with her information I went on to broadcast a series of stories about the company. Over several weeks I took it as far as the federal minister for immigration. He ordered an audit of the company and a review of all future contracts. I eventually won an ABC media prize for my work.’

‘This experience serves as a reminder that the Dominican network will find you when you least expect it. In fact, it probably never leaves you alone. Here was a nun from 40 years ago walking back into my life insisting that I live true to the Veritas motto. That fighting Dominican dedication to tell the truth and to advocate on behalf of those less privileged has shaped my personal value system and driven many work choices.’

That speech night she enthusiastically said: ‘Age is no barrier. At 54, I think my best work is yet to come. I really do.’

She felt so lucky to be a mature woman working in the media at that time in history. It was a period of particularly creative work for her. Apart from the award winning refugee series, she produced the Meet the Mob series.

‘When I moved to Newcastle in 2009, someone told me there weren’t many Aboriginal people here. How wrong they were! Outside of western Sydney, the Hunter has the second biggest population of Aboriginal people in New South Wales. But where were they? And why did we barely know them at ABC Newcastle?’

Jill made 100 ground-breaking interviews for the series, later turned into podcasts, with Indigenous Australians from the Hunter area. She was also a Walkley award finalist for her radio series Hooked on Heroin about a heroin crisis in the Hunter Valley.

Yes, she had the dream radio job and a devoted and growing fan base. Her only child, Malia, was now a young woman of whom Jill was so, so proud. And she had recently met a man she could spend the rest of her life with – Ken Lambert, a Newcastle GP who shared so many of her values.

But in February 2016, when Jill was only 56, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

‘How can this be happening to me?’ Let’s be honest, she didn’t just say this. She yelled it, screamed it and sobbed it – often in the arms of our school friend Donna Hensley, who had settled in Newcastle too, and supported her through many doctors’ visits. Jill had so much still to do, so much to live for.

At first Jill thought she could fight it – there was a lot in life she had fought by now, and she’d had plenty of wins. She had surgery: ‘peep and shriek’ as she described it because surgeons see such advanced cancer when they operate for this one that they scream. And she started chemotherapy, all the while hoping to get back to work.

Jill was struck by the vast differences in the survival rates of women with ovarian cancer compared to breast cancer. Only 46 per cent of women with ovarian cancer were still alive after five years, compared to 91 per cent of those diagnosed with breast cancer.

Jill realised ovarian cancer was overlooked.

In Jill’s own words, in one ABC interview she later gave: ‘I guess once I met other women with this disease I realised that there was a desperate need for this story to be known. A desperate need to kind of catch up with the awareness and success, better outcomes of our bigger sister disease and that’s breast cancer.’

Angry and alarmed, Jill decided to use her media skills and start fighting. It was as if the poet Dylan Thomas was whispering right in her ear when he said: ‘Do not go gentle into that good night…rage, rage against the dying of the light.’

And so began Jill’s very public brawl with this disease. For a long time she fought, refusing to accept that it would kill her – refusing to look at that.

Jill co-founded ‘Pink meets Teal’, with three other women from Newcastle – its main purpose – ‘social disruption’ – a very Jill expression. Pink meets Teal’s charter is to reach the goal of 100,000 signatures on a petition to create a permanent funding stream for ovarian cancer research, and she used her media savvy to bring attention to it. (It has nearly reached this goal.)

She shared a deeply personal story, through the making of the podcast series

Still Jill, in which she openly revealed the struggle she now faced, interviewing doctors, patients and others for this award winning podcast. She gave everything to this – since, as she pointed out, she had nothing to lose.

Jill shared with her listeners that as a secondary to the ovarian cancer, ‘a tumour the size of an egg on my brain,’ felled her one morning as she was getting out of bed. She joked that she had put the bad driving this had caused down to struggling with a new car.

She detailed how she went on several drug trials, only to be repeatedly bitterly disappointed. New work with immunotherapy was delivering breakthroughs for women, even with stage four cancer, like hers. But Jill watched, supported, congratulated other women she was now close to, as they had success with these treatments that she did not.

She struggled with this, admitting how hard it was. And yes, she could be a bit of a diva – so there were moments when she didn’t take it at all well. But she turned this into fuel for campaigning.

Jill addressed the National Press Club, in June 2018, to raise awareness for Ovarian Cancer, calling for funding equity for breast cancer and ovarian cancer: ‘After all, they’re both our girly bits.’

With tears streaming down her face, she said: ‘Despite all of the positive messages of hope and encouragement, I now know that this disease is going to kill me.’

And she made a brutal comparison between breast and ovarian cancer advocates: ‘We simply don’t live long enough to speak out and form our own army of advocates. We die, and we die quickly.’

On the same visit she banged on Minister For Health, Greg Hunt’s door, recording all the while for Still Jill.

‘I’m here to ask for more funding for ovarian cancer,’ she said.

And she got it. In a major victory in September, just before Jill died, she found out that because of her work, Minister Hunt was granting an additional $20 million for Ovarian Cancer research.

But while she celebrated, Jill realised that the $20 million was only a one off, that would be dispersed in tranches of $5 million over the following four years.

Jill knew we needed more. So what next? She wrote to Minister Hunt two days before she died. She expressed appreciation but pleaded for the $20 million to be turned into an annual, recurring, grant of at least $50 million per year.

She worked with the Ovarian Cancer Foundation. Her face shines from a provocative poster which says: ‘Ovarian Cancer will take my life. But it will not take my voice.’

And Jill’s life was about the voice, the spoken word, her voice, the voice of protest.

After marrying Ken, in September 2018, at a wonderful ceremony that brought together all the members of her Tongan and Aussie families, Jill spent time travelling through Europe. Around this time Jill also went to Tonga for more spiritual connection with that place. And there she met up with the cousin who would later prepare her ‘Apo’, the Tongan ritual that would be held the night before her funeral, an intimate moment that brought people together to sit in a circle and share stories.

Rev Garry Dodd, a close friend of Ken’s who had married Ken and Jill only a year before, led an extraordinary funeral service, the next day, on 18 December 18 2019.

‘It’s not a celebration, so I want everyone to wear black,’ she told her mother and others.

And Sr Diana Santelben gave the opening eulogy.

Jill’s greatest regret was to leave her young daughter Malia behind. She would not see Malia’s children.

Jill’s goal of shaking up the world of ovarian cancer funding still stands today. In June this year she was awarded an OAM, posthumously, for ‘service to people with Ovarian Cancer’.

‘And she would have got a real thrill for receiving that OAM,’ her Mum Liz said, ‘It’s just such a pity she is not here to enjoy it.